Femmehood: The Unexpected Feminist Subtext of Boyhood (Film Review) by Alison Ross

In conversation with the Village Voice, director Richard Linklater said of “Boyhood,” his critically revered recent release: “… it could be Girlhood or Motherhood or Familyhood.”

While I disagree that the movie could also have been called “Girlhood,” I do agree it could have been called “Motherhood,” for the film focuses almost as intensely on the mother, played by Patricia Arquette in a sparklingly authentic manner woven with gossamer nuance, as it does on Mason, the titular character.

In order for it to be called “Girlhood,” Linklater would have had to sustain focus on Samantha, Mason’s sister, in the same way as on Mason. In the first half or so of the film, we see a lot of Samantha, played by Loralei Linklater, the director’s daughter, and are actually more captivated by her than Mason given that she is the emblem of sassy and feisty and therefore scene-dominant. Mason is, by contrast, quite and contemplative, which naturally relegates him a bit to the background.

By the time the characters have aged significantly, however, Samantha herself has become more of a background character. I am not sure why this is the case and it’s frustrating, to say the least. Is the idea behind her dwindling dominance that she merely grew up to be a more inhibited version of herself, or is it that Linklater wanted Samatha’s role to recede? In other words, was it a deliberate creative choice on the part of the actress and Linklater (who famously collaborates with rather than dictates to his actors), or was it Linklater’s sole decision as autocratic autere? Either way, it’s a disappointing development in this otherwise nearly blemish-free film.

But as frustrating as that may be, the good news is, Patricia Arquette as admirable matriarch, clocks plenty of screen time, and her storyline involving a series of relationship fiascos is so realistically presented that this very feminist dimension could be overlooked. We might wonder how a seemingly wise woman would resort to picking such lousy losers for her romantic partners, but then we remember that she is attempting to create a stable family after her young marriage and ultimate estrangement from her first husband, Jesse, with whom she mothered Mason and Samantha.

And, of course, her men are not conspicuously obvious losers from the outset; initially they seem to harbor the hallmarks of upright men who will provide responsibly for their families, unlike wayward Jesse. But as they devolve into alcoholism and abusive behavior, it becomes clear that the stress of balancing family and work encumber their better judgement, and they buckle under the load. That Aquette’s character navigates the tumult with more aplomb suggests an implicit espousal of Ashely Montague’s The Natural Superiority of Women, in which the author bluntly states that women are constitutionally stronger than men. In other words, women often steer through hardship more capably than men. This is not to say that many women don’t still buckle under pressure, just that frequently (as anecdotal evidence will tell you), women handle stresses more functionally.

Too, the movie suggests, women have to put up with more when it comes to rearing children and are often the victims not just of domestic abuse, but of the feral whims of men. In particular, Jesse feeds his man-child proclivities through his fascination with vintage cars and shirking his paternal duties. Sure, he’s loving and evolves into a more responsible parent (and less interesting persona) by movie’s end, but clearly Linklater nourishes a cynical bias against his own gender.

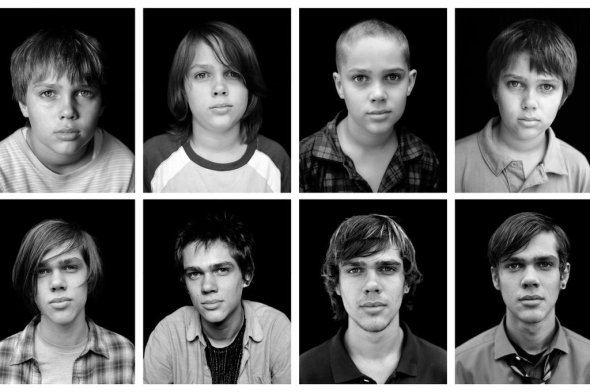

As all great movies do, Boyhood works on multiple levels concurrently, like a split-level house. In addition to the feminist subtext, and the obvious device (which never lapses into gimmickry) of filming over a 12-year period in order to capture Mason’s maturation in real-time, there is the technique of the movie itself which is subtly startling. What is most striking is how the temporal transitions are managed so transparently, and how everyday life details become larger than life – mundane minutia becomes magnified under Linklater’s microscope.

Like many past Linklater films such as “Dazed and Confused” and the “Before” trilogy, the verisimilitude is both jolting and comforting. We sink into familiar memory-spaces in our psyches upon observing Mason’s shifts into adolescence because we have been there, and the acting is so naturalistic, thanks to Linklater’s insistence on his actors sharing in script-writing. And we empathize with the mother’s travails all the more because her dramas are not hyperbolized, but rather, portrayed with understated pathos. This involves soft camera angles and fluid editing as much as it involves heartfelt acting.

Boyhood is mesmerizing and magical at the same time that it is raw and real, with unexpected feminist dimensions.

One Response to Femmehood: The Unexpected Feminist Subtext of Boyhood (Film Review) by Alison Ross

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Pingback: » Archive » ISSUE 29: REVIEWS AND INVECTIVE