Old Souls, But Just Kids (Book Review) by Alison Ross

I am chagrined to confess that Patti Smith has only very recently become one of my favorite musicians – she wasn’t even really on my radar until the past few years. I had known of her, obviously, and had heard few of her tunes, but her bohemian-punk aesthetic did not really appeal to me until now.

Smith is, first and foremost, a poet, and she is widely lauded for being from the same lineage as Rimbaud, lyrically speaking. And even her music is like the aural manifestation of a Rimbaud poem, with its gypsy gyrations and sinewy sounds that evoke murky corners in cobwebby caves. It’s not quite classic rock and it’s not quite punk rock, but a mystical merging of the two that engenders a nameless, elusive genre that brazenly defies tidy description.

Smith’s singing voice carries the lilting expressiveness of a gospel warbler and the commanding heft of Johnny Cash. Her deep undulating serenades are cosmically comforting and yet import a sense of earthly urgency. Indeed, if there is any way to delineate Patti Smith’s musical persona, it would be to say that it veers between the ethereal and the terrestrial. She is not seemingly of this world, but at her core she is inextricably connected with the tree roots, burrowed deep into the plush soil.

Smith poetic incantations foreshadowed a propensity for novel writing, to be sure, but was she up to the task of penning an engaging autobiographical tome? Autobiographies are often written in a dry, sterile manner, laden with details not of immediate interest to anyone but the most fanatical of fans. Writers can overcome some of these pitfalls by injecting a more poetic language and censoring uninspiring material in favor of that which hooks the reader in, like the catchiest songs.

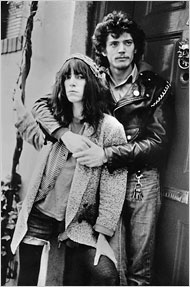

And this is exactly how Smith approached her book project that regales the tales of her young relationship with the legendary photographer, Robert Mapplethorpe. Her bookcraft mimics her songcraft: Intricate and intimate, and yet woven with effortless ease. There are abundant layers to her early life, and she peels these off in a metaphysical manner to reveal the rich existence of two gifted artists whose years of toil and turmoil culminate in recognition beyond their most vivid imaginings.

Smith’s prose is mostly unadorned – more straightforward than the Rimbaudian ramblings in her songs and poetry. And yet, the spacious feeling that her prose imparts allows us to read between the lines. She does not dictate to us the fevered dreams and emotional upheavals that inevitably accompany a struggling artist’s situation. And we are grateful to her for that: Her restraint yields a stronger empathy with her efforts and battles. She calmly relates her story and we calmly listen and absorb, like schoolchildren enraptured during reading circle time. And then we internalize her story and make it a part of our own.

What is most striking about the book is how magnetically drawn in we become by characters that may not mean anything to us at the outset. For example, I was hardly listening to any Patti Smith when I picked up her book, and was barely aware of her past. As for Mapplethorpe, I was only acquainted with the controversy of his “Piss-Christ” and with a few of his celebrity portraits. Beyond that, Mapplethorpe did not register significance in my life at all.

By the end of the book, Mapplethorpe had become a mild obsession for me, and Patti Smith’s music began heavy rotation on my turntable.

And New York City perhaps plays the most central role in the book. I will admit that I have, in recent years, become intrigued with the New York of the past, especially the 70s, since at that time it was at the forefront of the genesis of punk and hip-hop. New York City was at its peak creatively in the 70s and 80s, and Just Kids gives invaluable glimpses into what life in the city was like during this time.

So, yes, if you, like me, have been hankering to ascertain the burgeonings of artistic life in New York City, this book will satiate that craving – yet also leave you hungering for more. The scenes in the Chelsea Hotel and Patti Smith’s various hobnobs with artistic, musical and literary heavyweights are particularly precious.

And even if you, like me previously, have not given much thought to Patti Smith and Robert Mapplethorpe before, no worries: you will learn to love them – not as artists, but as people. For even though their respective art products merit much adoring scrutiny, it’s the creators whose juvenile struggles and passions resonate with us so richly and cause us to become so entranced with them. Oh, to spend a day at the cafe with Patti and Robert!

Sadly, Robert Mapplethorpe died of AIDS in 1989. Just Kids is gorgeous homage to his memory, and a compelling read for anyone who gives a damn about artful living.

One Response to Old Souls, But Just Kids (Book Review) by Alison Ross

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Pingback: » Archive » ISSUE 29: REVIEWS AND INVECTIVE